4 Heart

4.1 Preamble

Heart transplantation is a highly effective, final therapeutic option for patients with end-stage heart disease of varying aetiologies. Over 6,000 heart transplants are performed annually worldwide1 with over 120 heart transplants performed in Australia and New Zealand each year.21 Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1035-1049. ×2 ANZOD Registry. 2022 Annual Report, Section 7: Deceased Donor Heart Donation. Australia and New Zealand.Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2023. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au ×

Heart transplant recipients in Australia and New Zealand have a one-year post-transplant survival of 87.2%; 49.3% will survive for 15 years or longer and just over a third of all heart transplant recipients survive longer than 20 years.2 This compares with an average survival of less than two years for eligible patients who do not receive a heart transplant.32 ANZOD Registry. 2022 Annual Report, Section 7: Deceased Donor Heart Donation. Australia and New Zealand.Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2023. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au ×3 Chan YK, Tuttle C, Ball J, Teng TK, Ahamed Y, Carrington MJ, et al. Current and projected burden of heart failure in the Australian adult population: a substantive but still ill-defined major health issue. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16(1):501. ×

Current Australian estimates are that 30 000 patients are diagnosed with incident heart failure annually and that close to 500 000 people are living with long-standing chronic heart failure (CHF). 2 Between 2006 and 2011, deaths from CHF in Australia rose by 20%.3 The prognosis for CHF remains poorer than for common forms of cancer.4 Importantly, CHF is 1.7 times more common and occurs at a younger age among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples than among other Australians. Death rates and hospitalisation for CHF are also significantly higher in these groups. 42 ANZOD Registry. 2022 Annual Report, Section 7: Deceased Donor Heart Donation. Australia and New Zealand.Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2023. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au ×3 Chan YK, Tuttle C, Ball J, Teng TK, Ahamed Y, Carrington MJ, et al. Current and projected burden of heart failure in the Australian adult population: a substantive but still ill-defined major health issue. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16(1):501. ×4 Baumwol J. “I Need Help”-A mnemonic to aid timely referral in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017 May;36(5):593-594. ×4 Baumwol J. “I Need Help”-A mnemonic to aid timely referral in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017 May;36(5):593-594. ×

4.2 Recipient eligibility criteria

4.2.1 Assessment and acceptance

Heart failure clinicians caring for potential transplant candidates should discuss referral with one of the heart transplant centres in Australia and New Zealand (see Appendix H) and, when appropriate, arrange for timely referral.4 Paediatric patients will be referred to one of the three paediatric heart transplant centres, located within Victoria, New South Wales and Auckland. Early referral for heart transplant assessment is recommended to optimise time for thorough evaluation of the inclusion criteria outlined in Section 4.2.2. Early referral helps to facilitate transplant education for patients and their caregivers as well as allowing time to address barriers to transplant, which may include obesity, physical frailty, malnutrition, inadequate social supports, with pre-transplantation intervention.4 Baumwol J. “I Need Help”-A mnemonic to aid timely referral in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017 May;36(5):593-594. ×

On referral to heart transplant units, simultaneous referral to palliative care services is highly recommended to support the patient’s journey through transplant assessment, potential waitlisting, heart transplantation surgery, and their post-transplant life. The decision to waitlist a patient for heart transplantation is at the discretion of the transplant centre and their multidisciplinary team who are involved with the transplant assessment ‘work-up’ process.

Symptomatic end-stage cardiac conditions

The list below summarises the potential cardiac conditions that may be suitable for referral for heart transplant assessment. Upon referral for transplant assessment, patients need to have exhausted all alternative treatment options and have an expected survival benefit with reasonable prospect of returning to an active lifestyle.

End-stage heart disease, usually secondary to ischaemic heart disease or dilated cardiomyopathy with severe systolic dysfunction

Severe systolic dysfunction secondary to valvular heart disease

Diastolic dysfunction secondary to restrictive or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Heart failure secondary to congenital heart disease

Other conditions including specific heart muscle disease (other acquired, inherited) and those with intractable arrhythmias or intractable angina with no revascularisation option.

4.2.2 Inclusion criteria

Patients with one or more of the following criteria should be considered for heart transplant assessment:55 National Health Service Blood and Transplant Service UK :POL229/10 – Heart Transplantation: Selection Criteria and Recipient Registration, March 2023. Available at: https://www.odt.nhs.uk/transplantation/tools-policies-and-guidance/policies-and-guidance/ ×

Persistent New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III/IV symptoms despite optimum medical therapy (including cardiac resynchronisation therapy, CRT, if indicated)

Peak VO2 <14 ml/kg/min or <50% predicted in diagnostic cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET)

Unable to complete satisfactory CPET because of cardiac status

B-Type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) persistently >400 pg/ml or N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) >1600 pg/ mL, or increasing despite treatment

Low cardiac index (<2 L/min/m 2 )

Two or more admissions with decompensated heart failure in last 12 months despite adequate medical therapy and adherence

Heart Failure Survival Score of medium- to high-risk, or Seattle Heart Failure Model one-year estimated survival < 80%

Deteriorating WHO Group II pulmonary hypertension

Deteriorating renal function due to cardiorenal syndrome

Persisting hyponatraemia (<130 mmol/L) despite optimum medical treatment

Recurrent ventricular arrhythmia despite drug, ablation and device treatment

Intractable angina despite optimum medical, interventional and surgical treatment

Deteriorating liver function due to right heart failure despite optimum medical treatment

Persistent/recurrent symptomatic pulmonary oedema or serious systemic congestion despite optimum medical treatment.

In addition to the above, patients with acute or acute-on-chronic heart failure requiring durable mechanical circulatory support (MCS) such as a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) should be considered for transplant candidacy. Detailed guidance on MCS, including candidacy, can be found within The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) 2023 Guideline update.66 Saeed D, Feldman D, Banayosy AE et al. The 2023 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for Mechanical Circulatory Support: A 10- Year Update. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Jul;42(7):e1-e222. ×

4.2.3 Recipient characteristics associated with post-transplant outcomes

Careful evaluation is recommended for potential heart transplant recipients who may display additional risk factors such as older age, and/or impaired renal function, as detailed below. The following list summaries one-year survival rates as per the 2021 ISHLT Registry Report which focused on recipient characteristics.11 Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1035-1049. ×

Age: one-year survival is lower in recipients aged >60 years compared to younger age groups in Europe, one-year survival for recipients aged >60 years is 75% compared to 86% for recipients aged 18-39; in North America, one-year survival for recipients >60 years is 88% compared to 90% for recipients aged 18-39, in other countries

Kidney Function: one-year mortality exceeds 20% in patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 ml/min/1.73m 2 at transplant, which lends evidence in support of simultaneous heart-kidney transplantation in these candidates. Patients on pre-transplant dialysis have high one-year mortality, which supports consideration of simultaneous or staged heart-kidney transplantation in these patients

Mechanical support: one-year survival in LVAD recipients approximates that of non-LVAD recipients; but is lower in patients supported with biventricular assist device (BiVAD) and total artificial heart (TAH)

Gender: lower recipient survival is observed where there is a donor-recipient gender mismatch (female donor to male recipient)

Diabetes mellitus: five-year survival of recipients with diabetes has generally improved over time but remains inferior to that of patients without diabetes

Body Mass Index (BMI): higher recipient BMI (>26 kg/m 2 ) at the time of transplant is significantly associated with increased risk for one-year mortality.

Sensitisation is not a factor in one-year survival. Sensitised patients, defined as Calculated Panel Reactive Antibody (cPRA)score > 80%, is similar to that of non-sensitised patients. Prior malignancy does not appear to influence short-term (one and five year) post-transplant survival.11 Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1035-1049. ×

4.2.4 Exclusion criteria with considerations

Exclusion criteria include any condition or combination of conditions that would result in an unacceptably high mortality risk from heart transplant surgery, significantly and adversely affect post-transplant survival, or preclude active rehabilitation after transplantation.7-9 If present, appropriate measures to reverse, treat and support should be undertaken in a multidisciplinary approach to enable potential candidacy.7 Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: a 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2016;35(1):1-23. 8 Macdonald P. Heart transplantation: who should be considered and when? Intern Med J, 2008;38(12):911–17. 9 Russo MJ, Rana A, Chen JM, et al. Pretransplantation patient characteristics and survival following combined heart and kidney transplantation: an analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing Database. Arch Surg, 2009;144(3):241–46. ×

Major exclusion criteria for heart transplantation are as follows:

Active malignancy:7,10,11 an active malignancy, other than non-melanoma skin cancers, is usually a contraindication to heart transplantation; however, patients in permanent remission—as evidenced by prolonged disease-free survival—may be suitable for transplantation. With the availability of new cancer treatments this is an area undergoing rapid change. Best practice as to whether cancer treatment is required at all is also evolving; for example, low-risk, clinically localised prostate cancer may not need to be treated and ‘cured’ prior to the patient being considered eligible for heart transplantation. The decision as to whether or not to refer a patient with a history of malignancy for heart transplant assessment needs to be made on a case-by-case basis, and generally should only be made in consultation with the oncologist caring for the patient. In general, patients with a history of malignancy should only be considered for heart transplantation if their prior malignancy does not adversely impact their predicted post-transplant survival.7 Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: a 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2016;35(1):1-23. 10 Al-Adra DP, Hammel L, Roberts J et al. Pretransplant solid organ malignancy and organ transplant candidacy: A consensus expert opinion statement. Am J Transplant. 2021 Feb;21(2):460-474. 11 Campistol JM, Cuervas-Mons V, Manito N, et al. New concepts and best practices for management of pre- and post- transplantation cancer. Transplantation Reviews, 2012;26(4):261-279. ×

Complicated diabetes:12 patients with diabetes mellitus and established significant microvascular complications, poor glycaemic control (HbA1c >59 mmol/mol or 7.5%), or diffuse peripheral vascular disease are generally considered unsuitable for heart transplantation.7,12 On the other hand, patients with diabetes without secondary end-organ disease (proliferative retinopathy, nephropathy or neuropathy) have undergone heart transplantation with excellent long-term outcomes.12 Therefore, in patients with diabetes, optimisation of glycaemic control to achieve HBA1c < 7.5% is recommended prior to listing.12 Russo MJ, Chen JM, Hong KN, et al. Survival after heart transplantation is not diminished among recipients with uncomplicated diabetes mellitus: an analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. Circulation, 2006;114(21): 2280–87. ×7 Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: a 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2016;35(1):1-23. 12 Russo MJ, Chen JM, Hong KN, et al. Survival after heart transplantation is not diminished among recipients with uncomplicated diabetes mellitus: an analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. Circulation, 2006;114(21): 2280–87. ×12 Russo MJ, Chen JM, Hong KN, et al. Survival after heart transplantation is not diminished among recipients with uncomplicated diabetes mellitus: an analysis of the United Network of Organ Sharing database. Circulation, 2006;114(21): 2280–87. ×

Body Weight: several studies have identified obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 or ≥140% of ideal body weight) as an independent risk factor for mortality in heart transplant recipients,1,13-17 with one study reporting a doubling of mortality at five years post-transplant for patients with a BMI > 30 kg/m2. 11 In light of these published findings, morbidly obese patients should be required to reduce their weight below a BMI of 35 kg/m2 before being considered for heart transplantation.18 While cachexia (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) is not an exclusion criterion, it is also an important risk factor for poor clinical outcomes after heart transplantation.14 Emerging studies regarding prehabilitation, exercise, and nutrition interventions prior to cardiothoracic surgery have shown promising results with improved outcomes post-surgery.191 Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1035-1049. 13 Grady KL, White-Williams C, Naftel D, et al. Are preoperative obesity and cachexia risk factors for post heart transplant morbidity and mortality: a multi-institutional study of preoperative weight-height indices. Cardiac Transplant Research Database (CTRD) Group. J Heart Lung Transplant, 1999;18(8): 750–63. 14 Grady KL, Frazier OH, Bourge R, et al. Post-Operative Obesity and Cachexia Are Risk Factors for Morbidity and Mortality After Heart Transplant: Multi-Institutional Study of Post-Operative Weight Change for the Cardiac Transplant Research Database Group J Heart Lung Transplant, 2005;24:1424–30. 15 Weiss ES, Allen JG, Russell SD, Shah AS, Conte JV. Impact of recipient body mass index on organ allocation and mortality in orthotopic heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009;28:1150-7. 16 Russo MJ, Hong KN, Davies RR, et al. The effect of body mass index on survival following heart transplantation: do outcomes support consensus guidelines? Ann Surg 2010;251:144-52. 17 Macha M, Molina EJ, Franco M, et al. Pre-transplant obesity in heart transplantation: are there predictors of worse outcomes? Scand Cardiovasc J 2009;43:304-10. ×11 Campistol JM, Cuervas-Mons V, Manito N, et al. New concepts and best practices for management of pre- and post- transplantation cancer. Transplantation Reviews, 2012;26(4):261-279. ×18 Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, et al. International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Infectious Diseases, Pediatric and Heart Failure and Transplantation Councils. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: A 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016 Jan;35(1):1-23. ×14 Grady KL, Frazier OH, Bourge R, et al. Post-Operative Obesity and Cachexia Are Risk Factors for Morbidity and Mortality After Heart Transplant: Multi-Institutional Study of Post-Operative Weight Change for the Cardiac Transplant Research Database Group J Heart Lung Transplant, 2005;24:1424–30. ×19 West MA, Wischmeyer PE and Grocott MPW. Prehabilitation and Nutritional Support to Improve Perioperative Outcomes. Current Anesthesiology Reports. 2017;7:340-349. ×

Infection: patients with HIV, hepatitis B and C may be suitable for heart transplantation with careful consideration and management by the transplantation unit.20-24 This is described in more detail in Section 4.8 ‘Emerging Issues’.20 Escárcega RO, Franco JJ, Mani BC, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection. International Journal of Cardiology, 2014;175(1) 1-7. 21 Koval CE, Farr M, Krisl J, et al. Heart or lung transplant outcomes in HIV-infected recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019 Dec;38(12):1296-1305. 22 Chin-Hong P, Beatty G, Stock P. Perspectives on liver and kidney transplantation in the human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient. Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2013;27(2):459-71. 23 Cano O, Almenar L, Martinez-Dolz L, et al. Course of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection undergoing heart transplantation. Transplant Proc, 2007;39(7): 2353–54. 24 Potthoff A, Tillmann HL, Bara C, et al. Improved outcome of chronic hepatitis B after heart transplantation by long-term antiviral therapy. J Viral Hepat, 2006;13(11): 734–41. ×

Other infections—patients colonised with multi-resistant bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) have undergone successful heart transplantation; however, active systemic infection with these organisms would still be regarded as an absolute contraindication to heart transplantation. The decision regarding whether to refer patients with a history of chronic infection for heart transplant assessment needs to be individualised and generally should only be made in consultation with an infectious disease specialist and any other specialists caring for the patient. The exception to this would be a patient with an infected VAD where removal of the device at the time of transplantation may be potentially curative.

Non-adherence or inability to comply with medical advice and complex medical therapy:25-30 this includes chronic cognitive or neuropsychiatric deficits in the absence of a carer capable of taking on this role. Non-compliance with medical therapy after heart transplantation is a powerful predictor of increased morbidity and mortality.2725 Chacko RC, Harper RG, Gotto J, et al. Psychiatric interview and psychometric predictors of cardiac transplant survival. Am J Psychiatry, 1996;153(12): 1607–12. 26 Shapiro PA, Williams DL, Foray AT, et al. Psychosocial evaluation and prediction of compliance problems and morbidity after heart transplantation. Transplantation, 1995;60(12):1462–66. 27 Dobbels F, Vanhaecke J, Dupont L, et al. Pretransplant predictors of post-transplant adherence and clinical outcome: an evidence base for pretransplant psychosocial screening. Transplantation, 2009;87(10): 1497–1504. 28 Dew MA, DiMartini AF, De Vito Dabbs A, et al. Rates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ transplantation. Transplantation, 2007;83(7): 858–73. 29 Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Dobbels F, et al. The 2018 ISHLT/APM/AST/ICCAC/STSW recommendations for the psychosocial evaluation of adult cardiothoracic transplant candidates and candidates for long-term mechanical circulatory support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Jul;37(7):803-823. 30 Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Dobbels F, et al. The Approach to the Psychosocial Evaluation of Cardiac Transplant and Mechanical Circulatory Support Candidates. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2019 Dec;16(6):201-211. ×27 Dobbels F, Vanhaecke J, Dupont L, et al. Pretransplant predictors of post-transplant adherence and clinical outcome: an evidence base for pretransplant psychosocial screening. Transplantation, 2009;87(10): 1497–1504. ×

Non-compliance with recommended pre-transplantation vaccinations: the seroconversion rate after vaccinations is significantly higher in the non-immunosuppressed population compared to vaccination in immunosuppressed solid organ transplant recipients. It is therefore critical that potential transplant recipients are vaccinated before transplantation, to enable them to develop adequate immune responses to the pathogen.31 Rates of COVID-19 infection, severity of illness and mortality rates have been reported to be lower in the fully vaccinated transplant recipients, compared to non or partially vaccinated recipients.32-34 This highlights further the importance of adherence to transplant unit advice pertaining to recommended vaccination schedules.31 Velleca A,Shullo M.A, Dhital K et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Guidelines for the Care of Heart Transplant Recipients, Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation (2023). ×32 Yanis A, Haddadin Z, Spieker AJ, et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses to the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine among a cohort of solid organ transplant recipients and healthy controls. Transpl Infect Dis. 2022 Feb;24(1):e13772. 33 Schramm R, Costard-Jäckle A, Rivinius R, et al. Poor humoral and T-cell response to two-dose SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccine BNT162b2 in cardiothoracic transplant recipients. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021 Aug;110(8):1142-1149. 34 Aslam S, Adler E, Mekeel K, Little SJ. Clinical effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2021 Oct;23(5):e13705. ×

Active substance abuse:25,31 this includes smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and illicit drug use. Recommencing smoking after heart transplantation has been identified as a risk factor for accelerated coronary artery disease (CAD), malignancy, kidney failure, and poor post-transplant survival.35 For individuals with a history of substance abuse, a period of six months abstinence is strongly recommended (with confirmatory blood and/ or urine testing if considered appropriate) before active listing is considered.36 In the event of urgent clinical need, a shorter abstinence period may be considered if the patient shows motivation and compliance alongside a support network. Longer term support from the drug and alcohol services and/or support groups should also be implemented to ensure optimal post-transplant outcomes.25 Chacko RC, Harper RG, Gotto J, et al. Psychiatric interview and psychometric predictors of cardiac transplant survival. Am J Psychiatry, 1996;153(12): 1607–12. 31 Velleca A,Shullo M.A, Dhital K et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Guidelines for the Care of Heart Transplant Recipients, Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation (2023). ×35 Botha P, Peaston R, White K, et al. Smoking after cardiac transplantation. Am J Transplant, 2008; 8(4): 866–71. ×36 Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Steel J, et al. Meta-analysis of risk for relapse to substance use after transplantation of the liver or other solid organs. Liver Transpl, 2008;14(2): 159–72. ×

Irreversible degeneration/damage of other organ systems: this refers to any degeneration or damage that precludes rehabilitation after heart transplantation (e.g., advanced neurodegenerative disease, advanced rheumatoid arthritis, or severe peripheral vascular disease not amenable to revascularisation). In cases where there is irreversible failure of multiple transplantable organs, combined organ transplantation may be considered (see Section 4.7).37-39

Acute medical conditions: a number of acute medical conditions may render a person temporarily unsuitable for heart transplantation. These include active peptic ulcer disease, acute pulmonary embolism, and active systemic bacterial or fungal infection. Patients can be reconsidered for transplantation once these diseases have been resolved with appropriate medical therapy.

Frailty:40 frailty assessments should be performed in all patients with advanced heart failure who are being considered for heart transplant or LVAD. Whilst heart-transplant (and LVAD support) has been shown to reverse frailty post-transplant, prehabilitation is recommended to improve frailty status to enable candidacy.41,42 Pre-transplant frailty is a key indicator of poor post-transplant outcomes across all solid-organ transplants. In an Australian study of 140 heart transplant patients, frailty assessed using six domains (fatigue, grip strength, gait speed, loss of appetite, physical activity and cognitive assessment) within the six months prior to transplant surgery predicted poorer outcomes post-transplant.43 Frailty is also associated with increased mortality in patients undergoing BiVAD implantation, but not LVAD alone.44 Frailty is reversible following LVAD implantation, thus providing an improved foundation for heart transplantation.40 Denfeld QE, Jha SR, Fung et al. Assessing and managing frailty in advanced heart failure: An International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation consensus statement. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Nov 29:S1053-2498(23)02028-4. ×41 Ayesta A, Valero-Masa MJ, Vidán MT et al. Frailty Is Common in Heart Transplant Candidates But Is Not Associated With Clinical Events and Is Reversible After Heart Transplantation. Am J Cardiol. 2023 Oct 15;205:28-34. 42 Jha SR, Hannu MK, Newton PJ et al. Reversibility of Frailty After Bridge-to-Transplant Ventricular Assist Device Implantation or Heart Transplantation. Transplant Direct. 2017 May 30;3(7):e167. ×43 Macdonald PS, Gorrie N, Brennan et al. The impact of frailty on mortality after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Feb;40(2):87-94. ×44 Muthiah K, Wilhelm K, Robson D et al. Impact of frailty on mortality and morbidity in bridge to transplant recipients of contemporary durable mechanical circulatory support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022 Jun;41(6):829-839. ×

In summary, following assessment of physical frailty, cardiac rehabilitation is recommended in patients awaiting heart transplantation to decrease readmissions, waitlist mortality, and improve post-transplant outcomes.

Relative contraindications to heart transplantation include:

uraemia with calculated (or measured) GFR <40 mL/min 1,101 Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1035-1049. 10 Al-Adra DP, Hammel L, Roberts J et al. Pretransplant solid organ malignancy and organ transplant candidacy: A consensus expert opinion statement. Am J Transplant. 2021 Feb;21(2):460-474. ×

hyperbilirubinaemia >50 mmol/L 11 Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1035-1049. ×

intractable ascites with hypoalbuminaemia

fixed pulmonary hypertension with transpulmonary gradient (TPG) >15 mmHg or pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >4 Woods Units after pulmonary vasodilator challenge. 77 Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, et al. The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: a 10-year update. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2016;35(1):1-23. ×

These clinical characteristics identify individuals with a marked increase in post-transplant mortality regardless of whether there is evidence of intrinsic kidney, liver, or lung disease.1,10 Patients with evidence of renal and/or hepatic decompensation who otherwise meet eligibility criteria for heart transplantation, should be considered for MCS —so called ‘bridge to decision’45,46. Similarly, patients with fixed pulmonary hypertension should be considered for combined heart-lung transplant (see below) or long-term MCS, which has been shown to reverse pulmonary hypertension over a three- to six-month period in a large proportion of patients.46-481 Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1035-1049. 10 Al-Adra DP, Hammel L, Roberts J et al. Pretransplant solid organ malignancy and organ transplant candidacy: A consensus expert opinion statement. Am J Transplant. 2021 Feb;21(2):460-474. ×45 John R, Liao K, Lietz K, et al. Experience with the Levitronix CentriMag circulatory support system as a bridge to decision in patients with refractory acute cardiogenic shock and multisystem organ failure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2007;134(2): 351–58. 46 Etz CD, Welp HA, Tjan TD, et al. Medically refractory pulmonary hypertension: treatment with nonpulsatile left ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg, 2007;83(5): 1697–1705. ×46 Etz CD, Welp HA, Tjan TD, et al. Medically refractory pulmonary hypertension: treatment with nonpulsatile left ventricular assist devices. Ann Thorac Surg, 2007;83(5): 1697–1705. 47 Gorlitzer M, Ankersmit J, Fiegl N, et al. Is the transpulmonary pressure gradient a predictor for mortality after orthotopic cardiac transplantation? Transpl Int, 2005; 18(4): 390–95. 48 Muthiah K, Humphreys DT, Robson D et al. Longitudinal structural, functional, and cellular myocardial alterations with chronic centrifugal continuous-flow left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017 Jul;36(7):722-731. ×

4.2.5 Special circumstances and considerations

Heterotopic (piggy-back) heart transplantation

Historically, the vast majority of heart transplants have been performed orthotopically (i.e., the donor heart is implanted in the normal anatomical site of the recipient heart following its removal). Heterotopic or ‘piggy-back’ heart transplantation refers to the circumstance where the recipient heart is not removed and the donor heart is implanted in the chest and connected ‘in parallel’ with the recipient’s, so that the recipient now has two hearts pumping together. This may be considered in two clinical settings:

Fixed pulmonary hypertension : patients who meet the above eligibility criteria for heart transplantation and who have fixed pulmonary hypertension as evidenced by a TPG >15mmHg after vasodilator challenge, who are otherwise not deemed suitable candidates for durable mechanical circulatory support such as LVAD. 47,48 Suitable agents for assessing acute pulmonary vascular reactivity include intravenous glyceryl trinitrate, intravenous prostacyclin and inhaled nitric oxide. Paediatric patients with a high pulmonary vascular resistance may be considered for orthotopic transplantation based on the presence of acute reactivity, expected regression post-transplantation, the magnitude of the perioperative risk, and the availability of other treatment options.47 Gorlitzer M, Ankersmit J, Fiegl N, et al. Is the transpulmonary pressure gradient a predictor for mortality after orthotopic cardiac transplantation? Transpl Int, 2005; 18(4): 390–95. 48 Muthiah K, Humphreys DT, Robson D et al. Longitudinal structural, functional, and cellular myocardial alterations with chronic centrifugal continuous-flow left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017 Jul;36(7):722-731. ×

Higher-risk donors : where donor heart function is judged to be suboptimal for orthotopic transplantation (but the heart is still potentially recoverable), donors may be considered for heterotopic heart transplantation subject to informed consent of the potential recipient. 4949 Newcomb AE, Esmore DS, Rosenfeldt FL, et al. Heterotopic heart transplantation: an expanding role in the twenty-first century? Ann Thorac Surg, 2004;78(4):1345–50. ×

4.2.6 Retransplantation

Heart retransplantation is a rare occurrence in Australia and New Zealand, constituting only 1% of annual heart transplant procedures.2 Globally, retransplantation makes up around 2-3% of all heart transplants performed.50 The outcomes for heart retransplantation in cases of acute rejection and early graft failure are extremely poor.50-51 Therefore, these patients are generally not recommended for retransplantation. Conversely, ISHLT registry data indicate that specific patients undergoing heart retransplantation due to late graft failure secondary to cardiac allograft vasculopathy can achieve excellent short and long-term survival.50 In Australia and New Zealand, almost two-thirds of patients are alive at 15 years following retransplantation.2 Patients may be considered for heart retransplantation provided they meet standard eligibility criteria.2 ANZOD Registry. 2022 Annual Report, Section 7: Deceased Donor Heart Donation. Australia and New Zealand.Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2023. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au ×50 Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty- first official adult heart transplant report--2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2014;33(10):996-1008. ×50 Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty- first official adult heart transplant report--2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2014;33(10):996-1008. 51 Radovancevic B, McGiffin DC, Kobashigawa JA, et al. Retransplantation in 7,290 primary transplant patients: a 10-year multi- institutional study. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2003;22(8):862–68. ×50 Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty- first official adult heart transplant report--2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2014;33(10):996-1008. ×2 ANZOD Registry. 2022 Annual Report, Section 7: Deceased Donor Heart Donation. Australia and New Zealand.Dialysis and Transplant Registry, Adelaide, Australia. 2023. Available at: www.anzdata.org.au ×

4.3 Waiting list management

Heart transplant units will generally review patients listed for heart transplantation every 4-8 weeks in an outpatient clinic. This ongoing reassessment is critical to evaluate the patient’s changing status against predicted peri-operative or post-transplant outcomes. Repetition of some assessments such a physical frailty, echocardiogram, right heart catheterisation and serum/urine nicotine and other drug levels may be required by transplant units to ensure waitlisted patients still meet eligibility criteria for transplantation or to re-evaluate candidacy for MCS. Occasionally it may also be appropriate to de-list patients to consider supportive/palliative care pathways after discussion with the multidisciplinary team, the patient, and their caregivers.

4.3.1 Urgent patients

Under some circumstances — for example, when transplant candidates are deemed unsuitable for MCS, develop life-threatening complications while on support, and - if the patient’s estimated survival is deemed to be within days to a few weeks without transplant — the patient may be placed on an urgent list.

Urgent listing for heart transplantation is at the discretion of the Transplant Unit Director. It will be the responsibility of the Transplant Unit Director (or their nominee) to notify all other cardiothoracic transplant units in Australia and New Zealand and to notify all DonateLife Agencies across Australia and Organ Donation New Zealand when a patient is placed on (and removed from) the urgent waiting list. Donor hearts are offered to home state transplanting unit(s) first prior to offering to interstate urgent listing(s); it is at the discretion of each transplant unit to accept or decline a request for interstate urgent heart allocation. Urgently listed patients are to be considered prior to offering to paediatric transplant units as described in Section 4.6.2.

It is expected that the majority of individuals placed on the urgent waiting list will either die or be transplanted within two weeks of notification. In the event that a person remains urgently listed beyond two weeks, re-notification of all cardiothoracic transplant units and DonateLife Agencies is required at two-weekly intervals, as supported by the ADTCA-TSANZ-OTA National Standard Operating Procedure: Organ Allocation, Organ Rotation, Urgent Listing.

If there are simultaneously listed urgent patients, the following rule will apply:

If a compatible donor becomes available outside the state of the urgently listed patients, the heart will be offered to the home state transplanting unit first and then to the patient who was first listed as urgent (subject to the home state transplant unit(s) wavering the offer to the urgent listing(s)).

The operation of the urgent waiting list will be subject to annual audit and review by the Cardiac Transplant Advisory Committee (CTAC) of TSANZ.

4.3.2 OrganMatch

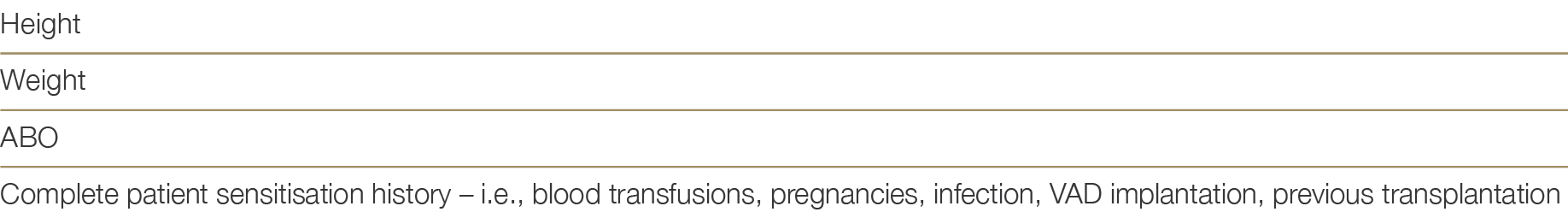

Patients listed for heart transplant must be registered on OrganMatch under the heart transplant waiting list program. Initial collection of blood samples are required for Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) typing and identification of HLA antibodies using solid phase technique (Luminex). Samples are collected monthly and HLA antibody testing will be performed. Whilst it is optimal for all waitlisted patients to be screened every three months, screening must have occurred within 120 days to be included in matching. Any sensitising event (i.e., blood transfusion) will require repeat HLA antibody testing in addition to the routine monthly sample. Clinical parameters required for the OrganMatch Heart algorithm, must be entered in OrganMatch by the clinical team or transplant unit at the time of listing. Table 4.0 shows the relevant clinical parameters.

Table 4.0: Essential Clinical Parameters required for the OrganMatch heart transplant waitlisting and algorithm.

In addition, the unacceptable antigen profile based on pre-defined criteria will be highlighted following consultation with the recipient transplant unit as described in Section 4.3.3 below.

4.3.3 Histocompatibility assessment

Each recipient must undergo a series of tests performed at the state Tissue Typing laboratories. This includes the following:

HLA typing using molecular technique such as Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) at the following HLA loci – A , B, C, DRB1, DQB1, DQA1, DPB1, DPA1

HLA antibody screening using Luminex single antigen beads. This screening must have occurred within 120 days to be included in matching.

These tests will be used in the histocompatibility assessment by the Tissue Typing labs and in consultation with the clinical unit to assign unacceptable antigens. These assigned unacceptable antigens can assist in excluding a waitlisted patient from incompatible donor offers.

4.3.4 Management of sensitised waitlisted patients

There has been a substantial increase in the transplantation of sensitised patients, with the percentage of recipients with a pre-transplant calculated panel reactive antibody (cPRA) of >20% increasing from 5.2% to 17%.1 This is reflective of the advances in antibody monitoring and management before and after heart transplants, especially with virtual crossmatching. There exists a fragile equilibrium in identifying unacceptable antigens in patients on the waiting list, potentially restricting access to organs for those with a designated ‘high’ cPRA. This cPRA serves as an estimate of the donor pool compatibility by assessing the frequency of antigens to be avoided due to the presence of corresponding cytotoxic antibodies. The most recent ISHLT Guidelines31 provide updated recommendations which are summarised in Table 4.1 below:1 Khush KK, Hsich E, Potena L, Cherikh WS, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult heart transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021 Oct;40(10):1035-1049. ×31 Velleca A,Shullo M.A, Dhital K et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Guidelines for the Care of Heart Transplant Recipients, Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation (2023). ×

Table 4.1: Management considerations of sensitised waitlisted patients3131 Velleca A,Shullo M.A, Dhital K et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Guidelines for the Care of Heart Transplant Recipients, Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation (2023). ×

Recipient histocompatibility assessment as per 4.3.3 above. When the cPRA is elevated (≥10%) further evaluation is recommended.

Each heart transplant centre should define the antibody threshold for unacceptable rejection risk. (In Australia, a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) less than 6,000 is the recommended acceptable threshold).

Determine and report the cPRA based on recipient antibody specificity and population antigenemic prevalence

Each heart transplant centre to define a cPRA threshold for desensitisation (i.e., >50%). Therapies aimed at reducing allosensitisation may be considered in selected patients where the likelihood of a compatible donor match is low or to decrease the risk of donor heart rejection where unavoidable mismatches occur.

If known, presence of non-HLA antibodies, such as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class I polypeptide-related sequence A (MICA) or angiotensin II type 1 receptor-activating antibodies (AT1R), antibodies to self-antigens are reasonable to report and consider when assessing antibody mediated rejection (AMR) risk

A complete patient sensitisation history including previous cPRA determinations is required to assess the risk of AMR.

The presence of anti-HLA antibodies can be reassessed 1 to 2 weeks following a sensitising event (such as blood transfusion) to reduce the possibility of positive cross match, including those undergoing desensitisation therapies.

4.4 Donor assessment

The majority of hearts donated for transplantation in Australia and New Zealand are obtained following donation after neurological determination of death (DNDD). The quality of donor hearts varies enormously, and historically fewer than 30% of hearts in the setting of DNDD have been considered suitable for transplantation. In 2014/2015, a series of successful heart transplants were performed using hearts retrieved following donation after circulatory determination of death (DCDD).52 Since 2014, the utilisation of donor hearts via the DCDD pathway has safely widened the donor pool, with excellent early,53 and mid-range outcomes at one-, three- and five-year follow-up being reported and comparable to that of hearts transplanted via the DNDD pathway.54,55 DCDD heart transplantation has become adopted as routine clinical practice for specialist transplanting centres (see Section 4.5 for further information on DCDD).52 Dhital KK, Iyer A, Connellan M, et al. Adult heart transplantation with distant procurement and ex-vivo preservation of donor hearts after circulatory death: a case series. Lancet, 2015; 385(9987):2585-91. ×53 Dhital K, Ludhani P, Scheuer S, Connellan M, Macdonald P. DCD donations and outcomes of heart transplantation: the Australian experience. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020 Aug;36(Suppl 2):224-232. ×54 Messer S, Rushton S, Simmonds L, et al. A national pilot of donation after circulatory death (DCD) heart transplantation within the United Kingdom. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Aug;42(8):1120-1130. 55 Messer S, Cernic S, Page A, et al. A 5-year single-center early experience of heart transplantation from donation after circulatory-determined death donors. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 Dec;39(12):1463-1475. ×

Another rapidly advancing area shaping cardiac transplantation in Australia and New Zealand is hypothermic ex-vivo machine perfusion utilising the XVIVO heart preservation system. International and Australian trials using the XVIVO have demonstrated the safe extension of the donor heart ischemic time and a reduction in the risk of primary graft dysfunction. See Section 4.8 for more information regarding advances in machine perfusion.

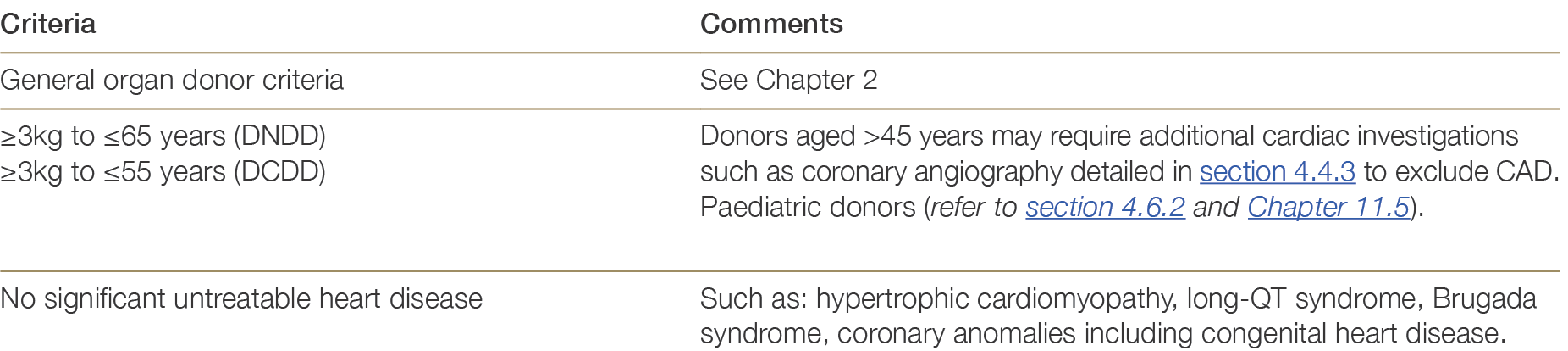

Table 4.2 below summarises the broad suitability criteria for donor heart referral to heart transplanting units across Australia and New Zealand. Additional factors impacting donor heart quality are outlined in Section 4.4.1.

Table 4.2: Suitability criteria for heart donation.

4.4.1 Donor related risk factors

Several donor-related and procedural variables are known to affect the quality of the donor heart. These include donor age, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, smoking), known heart disease in the donor prior to death, or injury to the heart after death.

Age: the risk of death after heart transplantation increases progressively with donor age greater than 30 years.56,57 A donor age of 50 years is associated with a 30% increase in the relative risk of death at one-year post-transplantation compared with a donor age of 30 years (an increase in the absolute risk of death at one-year post-transplant from 15% to 19%). The relative risk of death at one-year post-transplant rises to 50% for a donor age of 60 versus 30 years (absolute risk of 23% versus 15%).5056 Dayoub JC, Cortese F, Anžič A, Grum T, de Magalhães JP. The effects of donor age on organ transplants: A review and implications for aging research. Exp Gerontol. 2018 Sep;110:230-240. 57 Khush KK, Potena L, Cherikh WS et al.International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: 37th adult heart transplantation report-2020; focus on deceased donor characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 Oct;39(10):1003-1015. ×50 Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty- first official adult heart transplant report--2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant, 2014;33(10):996-1008. ×

ISHLT Registry data continues to demonstrate older donor age, especially ≥50 years, is associated with reduced post-transplant survival as early as one month after transplantation.57 Whilst globally the median age of donors is increasing, careful consideration is recommended in accepting hearts from donors older than 60 years due to the high risk of pre-existing CAD together with the heightened risk of cardiac allograft vasculopathy development.57 Khush KK, Potena L, Cherikh WS et al.International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: 37th adult heart transplantation report-2020; focus on deceased donor characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020 Oct;39(10):1003-1015. ×

DNDD vs DCDD: in DNDD, an intense sympathetic discharge that may occur during the development of brain death can result in severe (although usually reversible) myocardial dysfunction, as evidenced by a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) on echo, or a requirement for high doses of inotropic agents to maintain haemodynamic stability. In DCDD, warm ischaemic injury is an unavoidable consequence of withdrawal of life support. The duration of warm ischaemia is difficult to predict, however when this exceeds 30 minutes (from systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg to the administration of cardiac preservation solution) ischaemic damage to the heart is likely to be severe and not fully reversible.

Ischaemic time: the major procedural variable that affects donor heart quality is the ischaemic time—the interval between cross-clamp of the aorta in the donor (in the DNDD setting) and release of the aortic cross clamp in the recipient. The risk of death after heart transplantation increases progressively with ischaemic times exceeding 200 minutes. An ischaemic time of 360 minutes is associated with an 83% increase in the relative risk of death at one year post-transplantation (an increase in the absolute risk of death at one year post-transplant from 15% to 27%).58 There is a strong interaction between donor age and ischaemia time in their effect on transplant outcomes, and both variables need to be considered when deciding whether to accept a donor heart— particularly from an interstate or remote donor hospital when a prolonged transport time is anticipated. With donors > 45 years of age, it is recommended to avoid long-distance transportation, or other factors such as redo sternotomy, and VAD explantation—unless ex-vivo heart perfusion devices such as the XVIVO can be used to safely extend total donor heart ischaemic time.5958 Lund LH, Khush KK, Cherikh WS, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-fourth adult heart transplantation report-2017; focus theme: allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:1037–46. ×59 Copeland H, Knezevic I, Baran DA et al. Donor heart selection: Evidence-based guidelines for providers. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Jan;42(1):7-29. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2022.08.030. ×

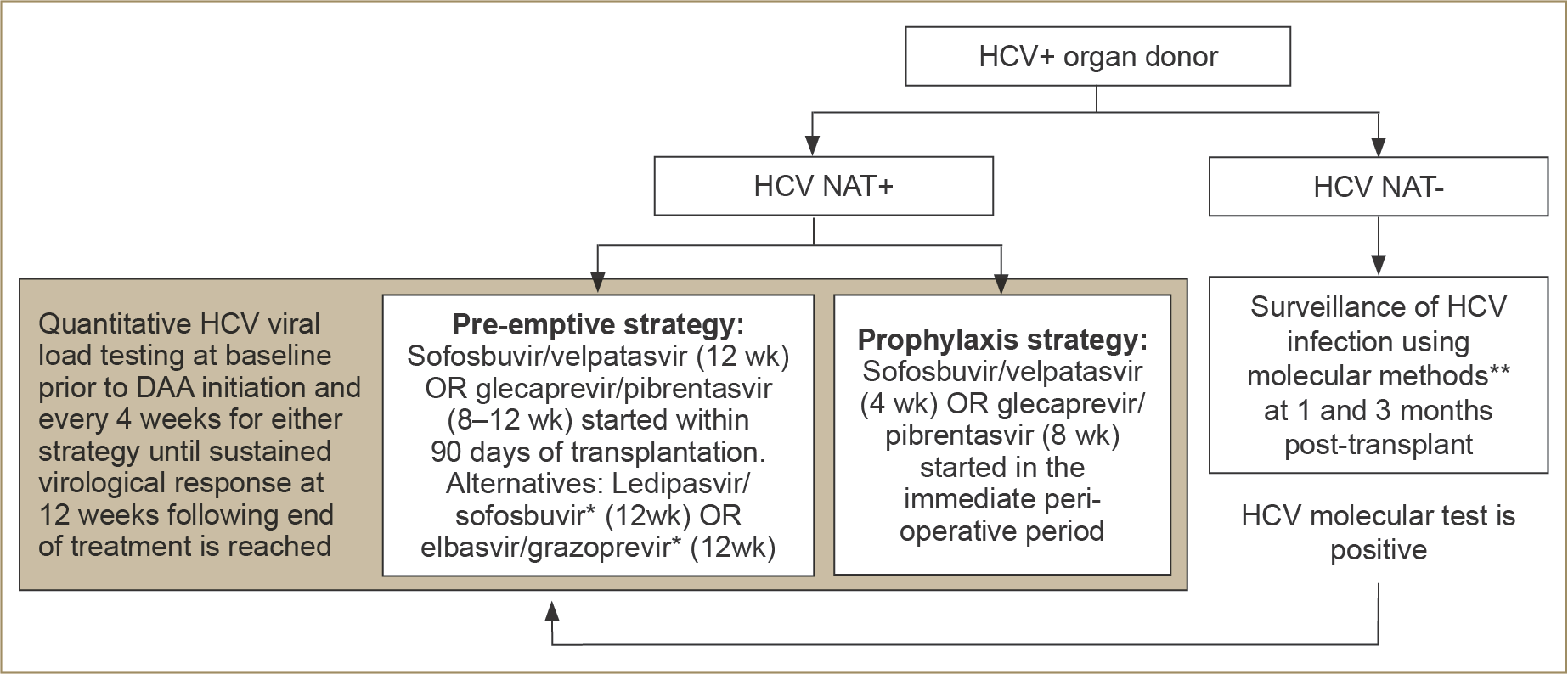

Infectious diseases: as with other solid organs transplanted from deceased donors, there is a risk of transmission of infectious diseases from donor to recipient (e.g. blood borne viruses such as HIV, hepatitis B or C). Donor screening for these and other transmissible diseases is discussed in Chapter 2. Screening may not detect all donor infections, including blood borne viruses recently acquired due increased risk behaviours.60 The decision to transplant organs from such donors should only be undertaken after careful consideration of the risks and benefits to the recipient and with the informed consent of the recipient (or senior next of kin in the event the recipient is unable to provide consent). Information pertaining to safety of transplanting organs from deceased donors with a history of Covid-19 can be found in Section 2.3.2.1, and is also supported by ISHLT 2023 Guidelines: Donor heart selection: Evidence-based guidelines for providers (jhltonline.org)5960 Gasink LB, Blumberg EA, Localio AR, et al. Hepatitis C virus seropositivity in organ donors and survival in heart transplant recipients. JAMA, 2006;296(15):1843-50. ×59 Copeland H, Knezevic I, Baran DA et al. Donor heart selection: Evidence-based guidelines for providers. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Jan;42(1):7-29. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2022.08.030. ×

It is expected that all heart transplant units in Australia and New Zealand will make use of all viable donor hearts. The acceptability of various donor types to potential heart transplant recipients should be discussed with both the patient and the patient’s carer at the time of waitlisting (rather than at the point of the heart offer). Informed consent should also be confirmed on the day of transplantation when there is a potential risk of transmission of donor infection (e.g. if the donor is positive for hepatitis B or C).

4.4.2 Donor information and testing

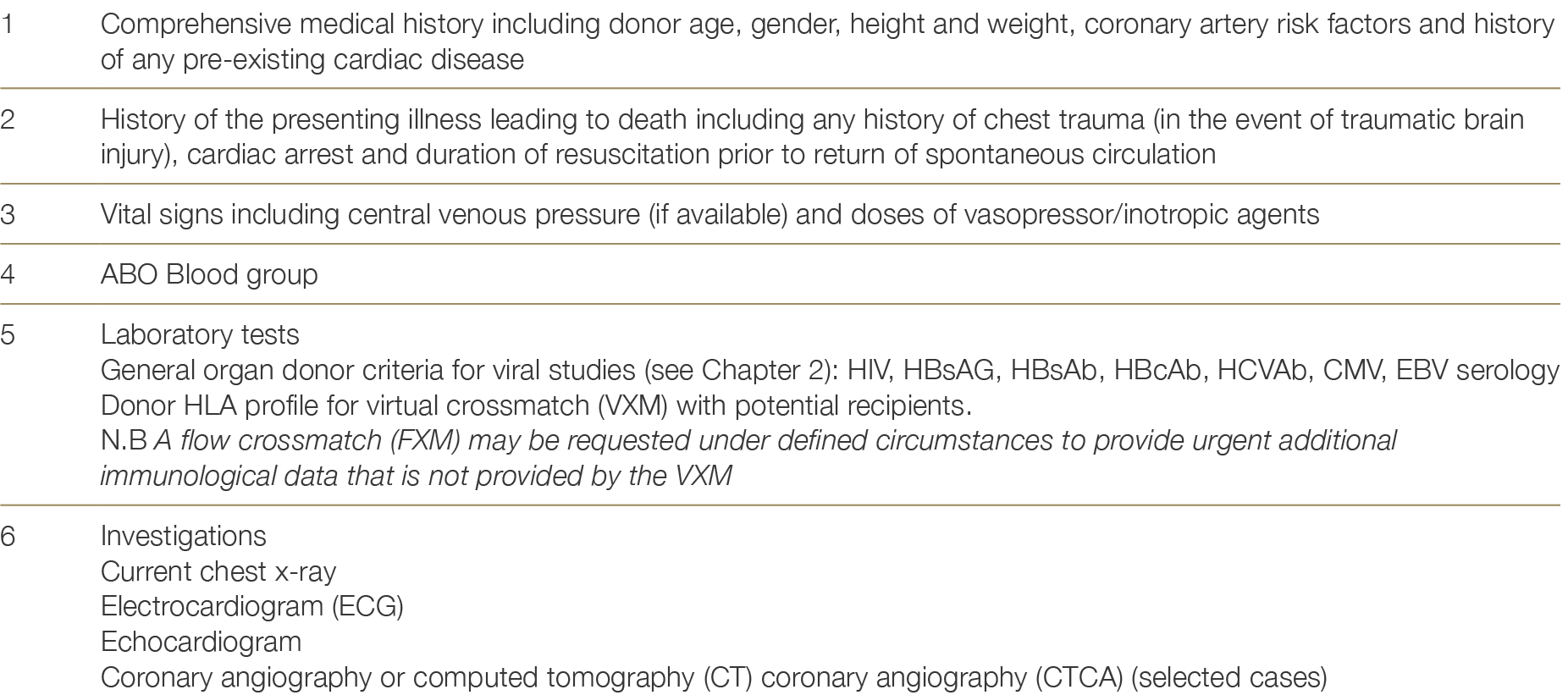

The assessment for heart donation suitability is outlined in Table 4.3.

Table 4.3: Donor information required for heart allocation.

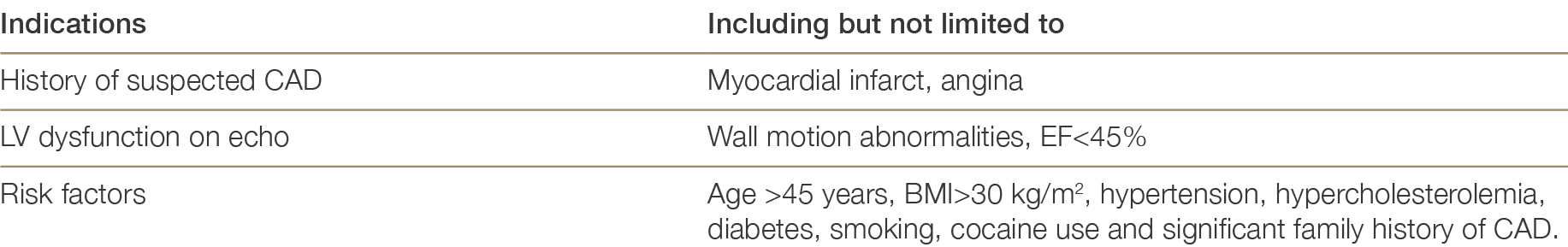

4.4.3 Donor coronary angiography

Donor coronary angiography has been associated with significantly better heart transplant outcomes compared to no angiography in donors at high risk of CAD.61 Moreover, the cost of donor coronary angiography is more than offset by the surgical retrieval costs avoided when a donor is found to have extensive coronary disease precluding heart transplantation.6161 Grauhan O, Siniawski H, Dandel M, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis of the donor heart – impact on early graft failure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 2007;32(4): 634-8. ×61 Grauhan O, Siniawski H, Dandel M, et al. Coronary atherosclerosis of the donor heart – impact on early graft failure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg, 2007;32(4): 634-8. ×

Coronary angiography should only be performed at the request of the heart transplant physician or surgeon and not solely upon the request of a transplant coordinator, as per the indications outlined in Table 4.4. This may necessitate direct communication between the heart transplant physician and the cardiologist/intensivist on duty at the donor hospital. Communication between the transplant physician and donor hospital will be facilitated by the transplant coordinator and the Donation Specialist Nurse Coordinator.

If a coronary angiogram is requested by the transplant physician/surgeon, this request should be made with a provisional acceptance of the heart pending an acceptable coronary angiogram result. If the heart is subsequently declined on the angiography result, national rotational offers should continue as per ADTCA-TSANZ-OTA National Standard Operating Procedure – Organ Allocation, Organ Rotation, Urgent Listing.

Right and left coronary artery angiogram is performed with minimal contrast. Investigations that should not be performed unless specifically requested are:

Left ventricular angiogram

Aortogram.

Coronary angiography should not be performed if:

The donor is physiologically unstable

There is a credible risk to the abdominal organs.

Table 4.4: Indications for coronary angiography5959 Copeland H, Knezevic I, Baran DA et al. Donor heart selection: Evidence-based guidelines for providers. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023 Jan;42(1):7-29. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2022.08.030. ×

4.5 Heart donation after circulatory determination of death

The use of Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (DCDD) hearts is reasonable at centres with: experience using marginal donor hearts, familiarity with the use of ex-vivo organ perfusion devices such as the Transmedics Organ Care System (OCS) for preservation and transportation, and experience instituting peri-operative mechanical support and its after-care for possible primary graft dysfunction.6363 Joshi Y, Scheuer S, Chew H, et al. Heart Transplantation From DCD Donors in Australia: Lessons Learned From the First 74 Cases. Transplantation. 2023 Feb 1;107(2):361-371. ×

DCDD heart transplantation normally occurs where cardiac arrest is expected after cardio-respiratory support is withdrawn in a controlled setting such as an intensive care unit (ICU) or operating theatre (Maastricht Category III donors).

Illnesses that can lead to a person being a potential DCDD heart donor include but are not limited to; irreversible brain injury (traumatic, cerebrovascular or hypoxic-ischaemic) where there is little or no possibility of deterioration to neurological death; severe respiratory or liver failure; ventilator-dependent quadriplegia; and advanced neuromuscular disease with respiratory failure.6464 Organ and Tissue Authority: Best Practice Guideline for Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (DCDD) in Australia, Edition 1.0, October 2021. Available at https://www.donatelife.gov.au/for-healthcare-workers/clinical-guidelines-and-protocols/ national-guideline-donation-after-circulatory-death ×

4.5.1 Withdrawal timing to candidacy

Patients who are consented and medically suitable to donate their heart for transplantation and in whom cessation of circulation is predicted to occur shortly after withdrawal of cardio-respiratory support (WCRS) will be considered for heart donation. WCRS in the setting of planned DCDD involves extubation with removal of mechanical ventilation and cessation of vasoactive agents (if present) provided for haemodynamic support, and/or removal of more advanced mechanical cardio-respiratory supports. This process should be performed in a controlled manner by the intensive care unit (ICU) staff, either in the ICU or in the anaesthetic bay of the operating room in which the surgical retrieval procedure is to take place. If hospital infrastructure and established protocols allow a choice of location, each option should be explained to the family along with any impact on their experience and possible impact on donation and transplantation outcomes (e.g. affecting warm ischaemic times and organ utilisation). WCRS in the operating theatre complex will facilitate a shorter duration between death determination and organ retrieval, minimising organ warm ischaemic injury, and is the preferred site of WCRS when donation of the heart (or liver) is planned.64 Following the onset of circulatory arrest, death is confirmed after five minutes of continuous absent pulsatility observed using intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring. The requirement is for mechanical asystole and not electrical asystole, noting that electrical activity may continue for many minutes after cessation of circulation. It is important to minimise warm ischaemic organ injury, so there should be prompt death confirmation after five minutes of absent circulation and followed by immediate movement of the patient to the operating theatre and table.6464 Organ and Tissue Authority: Best Practice Guideline for Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (DCDD) in Australia, Edition 1.0, October 2021. Available at https://www.donatelife.gov.au/for-healthcare-workers/clinical-guidelines-and-protocols/ national-guideline-donation-after-circulatory-death ×64 Organ and Tissue Authority: Best Practice Guideline for Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (DCDD) in Australia, Edition 1.0, October 2021. Available at https://www.donatelife.gov.au/for-healthcare-workers/clinical-guidelines-and-protocols/ national-guideline-donation-after-circulatory-death ×

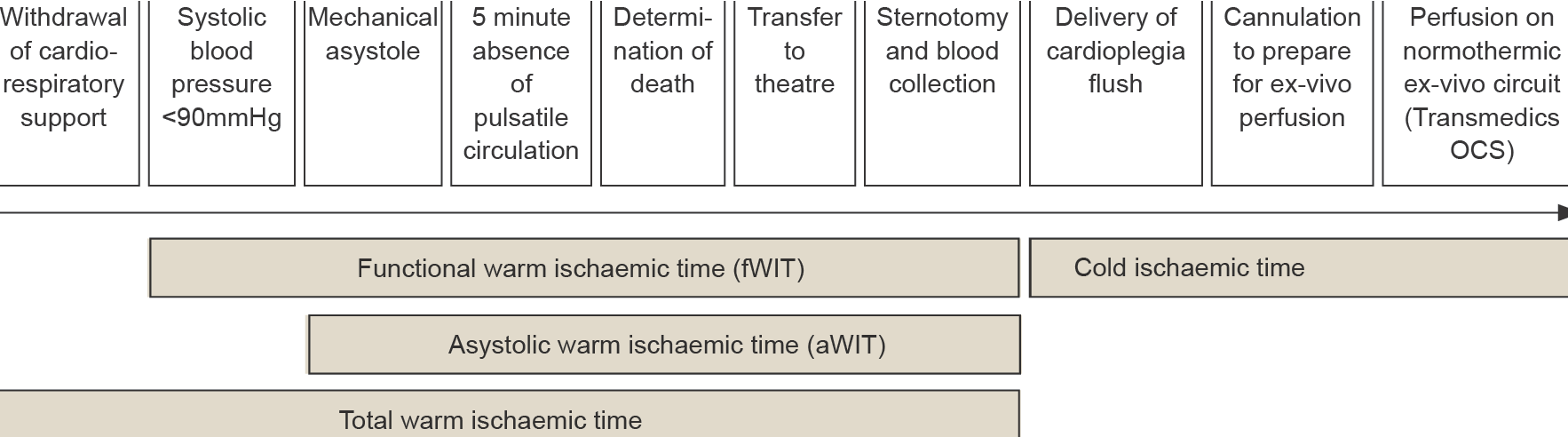

The heart is very susceptible to warm ischaemic injury and, although exact safe timeframes are uncertain, current practice is to not proceed with heart retrieval for transplantation if the functional warm ischaemia time (fWIT) is likely to exceed 30 minutes. The fWIT for the heart is taken to be the time following WCRS from when there is a sustained fall in systolic blood pressure (SBP) below 90 mmHg to the administration of cardiac preservation solution/cardioplegia. After WCRS, the time for the SBP to fall to below 90 mmHg can vary. It is possible for death to occur well beyond 30 minutes following WCRS and for there still to be a satisfactory fWIT. The DCDD process is usually stood down if death has not occurred within 90 minutes of WCRS. Prior to standing down the process, there should be communication between the surgical retrieval team and staff attending the potential donor in case death is imminent with acceptable ischaemic times still possible.6464 Organ and Tissue Authority: Best Practice Guideline for Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (DCDD) in Australia, Edition 1.0, October 2021. Available at https://www.donatelife.gov.au/for-healthcare-workers/clinical-guidelines-and-protocols/ national-guideline-donation-after-circulatory-death ×

The asystolic warm ischaemic time (aWIT) is part of the fWIT and is the time from loss of circulation (mechanical asystole) to the administration of cardiac preservation solution/cardioplegia. The time taken from the delivery of cardioplegia until normothermic reperfusion of the heart on the Transmedics OCS is considered the cold ischemic time (CIT), or “back-table CIT”, as it includes the time taken for back-table preparation of the heart before Transmedics OCS reperfusion. Figure 4.0 provides a schematic illustration of these timings.

Figure 4.0: DCDD timings for heart retrieval:6363 Joshi Y, Scheuer S, Chew H, et al. Heart Transplantation From DCD Donors in Australia: Lessons Learned From the First 74 Cases. Transplantation. 2023 Feb 1;107(2):361-371. ×

4.5.2 Antemortem interventions

Ante-mortem interventions are procedures that are undertaken on the patient prior to death for the purpose of organ donation. Specific consent would usually be obtained for trans-oesophageal echocardiography, bronchoscopy, femoral cannulation, and blood product administration. Blood transfusion prior to donation may be requested by the accepting transplant unit if the donor’s haemoglobin is < 100g/dL. A haemoglobin of > 100g/dL and a haematocrit of > 25% is desirable in order to facilitate delivery of warm oxygenated blood during normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) on the Transmedics OCS. The use of antemortem heparin is contingent on jurisdictional guidelines and hospital policy and is to be requested when permissible.6464 Organ and Tissue Authority: Best Practice Guideline for Donation after Circulatory Determination of Death (DCDD) in Australia, Edition 1.0, October 2021. Available at https://www.donatelife.gov.au/for-healthcare-workers/clinical-guidelines-and-protocols/ national-guideline-donation-after-circulatory-death ×

4.5.3 Donor blood collection

Post cessation of circulation, approximately 1.2 – 1.5L of donor blood is to be collected in a heparin primed bag before the administration of cardioplegia, in the retrieval theatre. The addition of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonist such as tirofiban can be considered to prevent leucocyte filter clotting.6363 Joshi Y, Scheuer S, Chew H, et al. Heart Transplantation From DCD Donors in Australia: Lessons Learned From the First 74 Cases. Transplantation. 2023 Feb 1;107(2):361-371. ×

The collected donor blood pH is usually <7.0 and partial correction to <7.2 (not to 7.4) with sodium bicarbonate should be performed. This is supported by pre-clinical studies demonstrating initial reperfusion of the ischaemic heart with an acidic perfusate reduced ischaemia-reperfusion injury.65,6665 Cohen MV, Yang XM, Downey JM. Acidosis, oxygen, and interference with mitochondrial permeability transition pore formation in the early minutes of reperfusion are critical to postconditioning’s success. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:464–471. 66 White C, Ambrose E, Müller A, et al. Impact of reperfusion calcium and pH on the resuscitation of hearts donated after circulatory death. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:122–130. ×

4.5.4 Donor heart viability assessment and lactate profiles

DCDD hearts are reperfused ex-situ using NMP systems such as the TransMedics OCS. Viability parameters include: (1) myocardial lactate extraction defined as a reduction in venous lactate levels compared to arterial lactate, (2) reduction in overall lactate, (3) visual inspection and, (4) haemodynamic parameters (mean aortic pressures between 65 and 90 mmHg; coronary flow between 650 and 950 mls/min on NMP).67,6867 Messer S, Ardehali A, Tsui S. Normothermic donor heart perfusion: current clinical experience and the future. Transpl Int. 2015;28:634–642. 68 TransMedics. TransMedics Organ Care System OCS Heart User Guide. 2021. Available at https://www.fda.gov/media/147298/ download ×

4.5.5 Controlled cooling

The heart on the Transmedics OCS is cooled at intervals of 2 °C (from 34 °C), by connection to a water heater cooler. Cold crystalloid cardioplegia (1 L) is administered once the heart has been cooled to 16 °C. The heart is then decannulated from the Transmedics OCS and placed in a bowl of ice and cold saline slurry for 15-20 minutes before implantation into recipient‚ This is to ensure adequate cold protection during the implantation process in the recipient. An additional dose of cold blood cardioplegia is administered immediately before the commencement of implantation, and further doses administered at 20- to 30-min intervals as needed during the implantation procedure.

4.6 Allocation

4.6.1 General allocation principles

The Donation Specialist Nurse Coordinator of the relevant jurisdictional DonateLife agency is responsible for referring potential cardiothoracic organ donors to the transplant coordinator for the corresponding heart transplant unit.

A donor heart is offered to the home state transplant unit first. When there are no urgently listed patients, donors who meet paediatric criteria (see Section 4.6.2 below), are offered to paediatric recipients first. Each jurisdiction across Australia and New Zealand has an assigned home state heart transplant unit as listed below:

If the home state heart transplant unit declines the offer, the donation offer is made on rotation to non-home state heart transplant units, with a 30-minute response time. For Victoria and New South Wales, both the adult and the paediatric heart transplant units must receive the offer before moving to the next state on the rotation.

Donor heart offers from South Australia and the Northern Territory are offered on rotation as for non-home state offers. Patients in South Australia or the Northern Territory who require heart transplantation are referred to interstate heart transplant units. New Zealand now receives donor heart offers from eastern states of Australia, and donor heart offers from New Zealand that are declined by the New Zealand heart transplant unit are offered to heart transplant units in the eastern states of Australia as per the ADTCA-TSANZ-OTA National Standard Operating Procedure: Organ Allocation, Organ Rotation, Urgent Listing.

4.6.2 Paediatric heart offering principles

All heart donors ≥17 years AND >50kg are to follow general allocation principles described above in Section 4.6.1. Donor hearts that are to follow the paediatric heart offering principles are defined as <17 years old AND/OR 3kg-≤50kg and are to be formally offered to paediatric recipients waitlisted at one of the three paediatric heart transplant units across Australia and New Zealand. Urgently listed patients are to be considered prior to the paediatric heart offering principles. Please refer to Appendix O for Paediatric Heart Offering Principles, as well as the ADTCA-TSANZ-OTA National Standard Operating Procedure: Organ Allocation, Organ Rotation, Urgent Listing.

4.6.3 Allocation algorithm

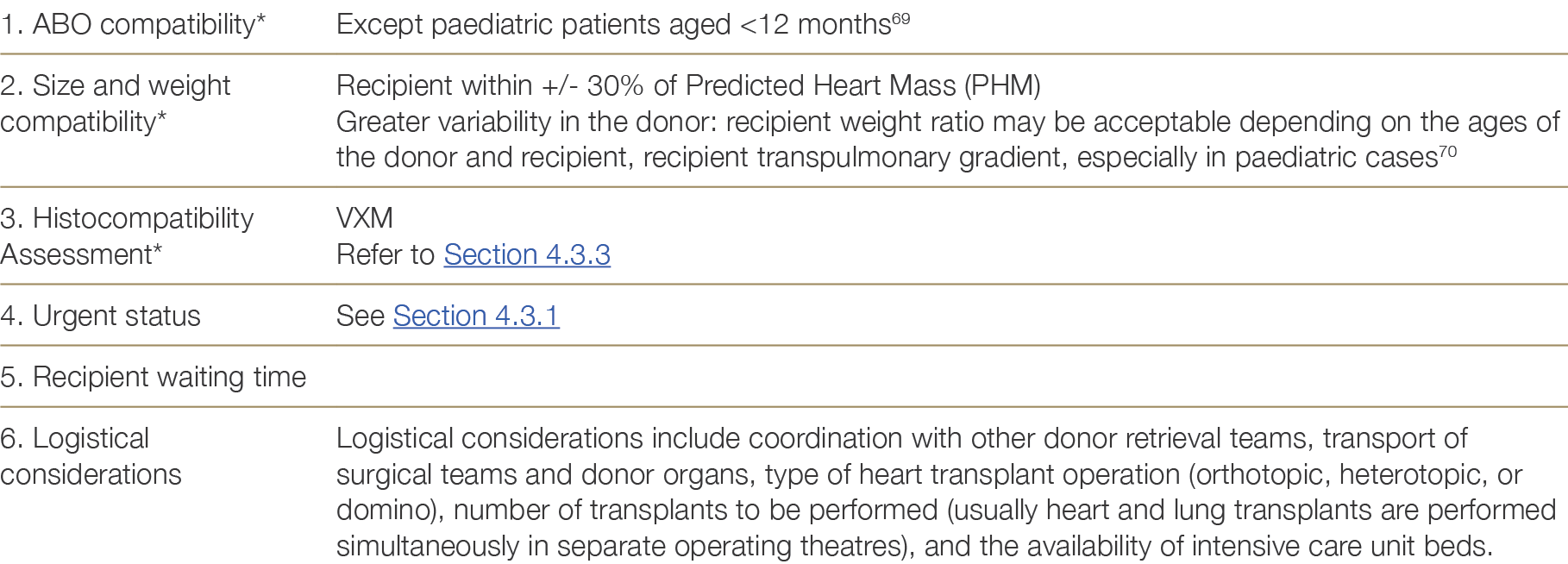

Donor hearts are allocated according to the criteria shown in Table 4.5 below. Decisions about each individual offer and waiting list management are the responsibility of the local heart transplant unit.

Table 4.5: Matching criteria for heart donation

Notes:

* Items 1–3 are absolute requirements for adult patients.

The OrganMatch Heart Transplant Waiting List (TWL) matching algorithm (See Appendix G) uses blood group compatibility, size matching (predicted heart mass) within a pre-specified perecentage range, and immunological compatibility to generate a list of potential recipients. The Tissue Typing Laboratory will perform Virtual Crossmatches (VXM) for the recipients on this potential recipient list. Patients with unacceptable antigens (above the pre-determined MFI threshold) to the donor HLA typing will be excluded from the match.

4.7 Multi-organ transplantation

Globally there has been an increase in the number of multiorgan transplants performed annually, although this still represents a small proportion of overall heart transplants. According to ISHLT registry data, multiorgan(heart-kidney, heart-liver) transplants comprised just over 3% of adult heart transplants whilst heart-lung transplants comprised 1.6% of adult lung transplants.71 Due to small numbers, outcomes data is limited to single centres and registries.71 Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1155-1168. ×

The following section will discuss the indications and risk factors associated with recipients receiving multiorgan transplants, the outcomes in recipients of multiorgan transplant, potential challenges regarding sensitisation and processes for listing for combined organ transplant. A recipient being considered for multiorgan transplantation needs to fulfil the eligibility criteria of both solid organs, with careful consideration of comorbidities and expected transplant survival.

4.7.1 Indications for multiorgan transplantation

Heart-lung transplant – Heart-Lung transplantation should be considered in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension with severe cardiac dysfunction or those with Eisenmenger physiology/complex congenital heart disease and irreversible pulmonary hypertension.7272 Chambers DC, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb SB et al.International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth adult lung and heart-lung transplant report-2018; Focus theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1169-1183 ×

Heart-kidney transplant – Patients with end stage heart failure often have concomitant kidney disease. The challenge lies in differentiating those patients with a significant component of reversible kidney injury due to cardiorenal syndrome who may recover after restoration of cardiac performance versus those with intrinsic advanced kidney disease who may benefit from a simultaneous heart-kidney transplant. Potential heart transplant recipients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease should be referred to a nephrologist for evaluation and discussion of prognosis and treatment.31 In a recent consensus conference on heart-kidney transplantation, it was felt that heart transplant candidates with an established GFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2 may be considered for simultaneous heart-kidney transplantation.73 An international heart/kidney workgroup also suggested that patients with established GFR of 30-44 ml/min/1.73m2 with firm evidence of chronic kidney disease such as small kidney size or persistent proteinuria >0.5 g/day may also be considered for simultaneous heart-kidney transplant on an individual basis.73 Recipients of multiorgan transplants had a higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes, potentially reflecting the higher incidence of renal dysfunction in patients with these diagnoses.7131 Velleca A,Shullo M.A, Dhital K et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Guidelines for the Care of Heart Transplant Recipients, Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation (2023). ×73 Chih et al. CCS 2020 guidelines. Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Cardiac Transplant Network Position Statement on Heart Transplantation: Patient Eligibility, Selection, and Post-Transplantation Care. ×73 Chih et al. CCS 2020 guidelines. Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Cardiac Transplant Network Position Statement on Heart Transplantation: Patient Eligibility, Selection, and Post-Transplantation Care. ×71 Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1155-1168. ×

Heart-liver transplant – The common indications for heart-liver transplant are advanced heart failure with cardiac cirrhosis seen primarily in congenital heart disease, heart failure with concomitant noncardiac cirrhosis, or advanced heart failure with associated liver disease in which the liver is transplanted to avoid ongoing damage to the cardiac allograft such as in familial amyloid neuropathy.73,7473 Chih et al. CCS 2020 guidelines. Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Cardiac Transplant Network Position Statement on Heart Transplantation: Patient Eligibility, Selection, and Post-Transplantation Care. 74 Lebray P, Varnous S. Combined heart and liver transplantation: state of knowledge and outlooks. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2019;43:123-30. ×

4.7.2 Processes for listing

Before patients are listed for combined organ transplantation, specific state transplant advisory committee (TAC) approval needs to be obtained. Patients being considered for heart-lung transplant will have their care primarily driven by the lung team with the thoracic organs implanted en-bloc. The decision for simultaneous versus sequential heart-kidney transplant is an individualised process with no current universally accepted criteria. Exploration and discussion for living kidney donation should occur contemporaneously with the evaluation process for heart-kidney transplant to maximise opportunities for evaluation and utilisation of such donors.7575 Kobashigawa J, Dadhania DM, Farr M, et al. Consensus conference on heart-kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:2459–2467. ×

4.7.3 Multiorgan transplant outcomes

Recommendations on the perioperative management of the multiorgan recipient and choice of induction and maintenance immunosuppression regimes have been previously outlined.71,31 The early post-operative course for multiorgan transplants is more complex than that for isolated heart transplants. Approximately 30% of heart-kidney and heart-liver transplant recipients were hospitalised for at least 1-month post-transplant, compared with 17% for heart only transplants.71 The incidence of severe renal dysfunction was similar in both the heart-kidney and the heart only transplant cohorts.7171 Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1155-1168. 31 Velleca A,Shullo M.A, Dhital K et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Guidelines for the Care of Heart Transplant Recipients, Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation (2023). ×71 Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1155-1168. ×71 Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1155-1168. ×

As per the 2018 ISHLT registry report, the incidence of acute rejection and development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) was lower after multiorgan transplantation compared with heart only transplantation (10% vs 24% for acute rejection, 24.3% vs 29.3% prevalence of CAV at 5 years).71 Although not well understood, this is postulated to reflect immune modulation that results from introduction of higher volume of donor hematopoietic elements to the recipient receiving multiorgan transplants.76,77 Overall survival was modestly improved in multiorgan transplant recipients, compared with heart only transplant recipients.71 Deaths due to infectious causes predominated after multiorgan transplantation, whereas deaths due to graft failure and malignancy were more common after heart only transplantation.7171 Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1155-1168. ×76 Pinderski LJ, Kirklin JK, McGiffin D, et al. Multi-organ transplantation: is there a protective effect against acute and chronic rejection? J Heart Lung Transplant 2005;24:1828-33. 77 Chou AS, Habertheuer A, Chin AL, Sultan I, Vallabhajosyula P. Heart-kidney and heart-liver transplantation provide immunoprotection to the cardiac allograft. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;108:458-66. ×71 Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1155-1168. ×71 Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018 Oct;37(10):1155-1168. ×

4.7.4 Retransplantation